Photography by Michael Shopenn

Building an eco-friendly dream home for about the same cost as a conventional home seemed daunting when my husband, Luke, and I bought three acres of Virginia forest nearly eight years ago. Our purchase came just before the dot-com crash (Luke owns a software company); shortly thereafter our funds would have evaporated.

Artist Anthony Brock's "Body of Paint" on recycled plastic hangs as if it were designed specifically for the space. The glass table and recyclable Panton chairs were purchased through Design Within Reach.

Believing fate was on our side, Luke, our two children and I set out

to build an environmentally conscious home for no more than

5 percent above the cost of a conventional one.

We set our goals high; we wanted to use green products, but they had to be cost competitive—within 5 percent of a comparable mainstream product. Luke and I vowed to limit waste by choosing a clean design style, ordering supplies conservatively and salvaging whenever possible. As a conservation policy consultant, I'm passionate about the environment, and our subcontractors began to understand my ardor when I climbed inside the Dumpster one day to retrieve a good piece of drywall.

A childhood friend of Luke's built the 8-square-foot table out of stainless steel and certified sustainable maple and walnut.

The plan takes shape

To disturb the natural landscape as little as possible, Luke and I planned for site preservation six months before construction began. We hired a professional arborist, RTEC Treecare, to assess the health of all trees within 50 feet of the project footprint. The company surrounded the entire impacted area with tree protection fencing and helped strengthen trees within 20 feet of the disturbance area with root aeration mats.

The fireplace has a recycled-concrete material, which is key to retaining and radiating heat in the great room during winter. The blue, Cassina "Dodo" chair reclines flat and has an optional footrest.

We worked with the company to develop a set of tree-protection rules, including financial penalties for violations, and made all contractors sign it before entering the job site. These tree-protection measures cost $34,000—about one-third of our total landscaping costs—but I consider it money well spent. It was an additional expense, but by contrast, our neighbors just finished construction without any tree-protection measures. They spent nearly $10,000 to fell three 100-foot trees killed by construction impact. We kept our beautiful trees—and their cool shade.

A custom, stainless steel fireplace the owners designed runs on natural gas. The blue sofa fabric by Knoll—which looks and feels like leather—is actually recycled polyester and nylon and wipes clean with a damp cloth.

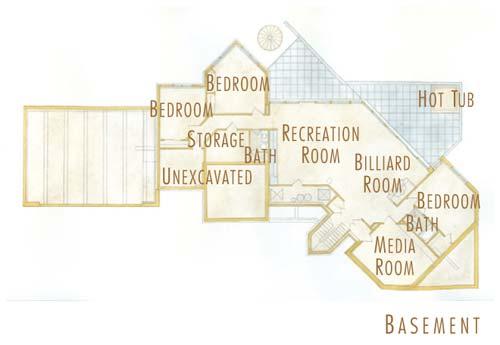

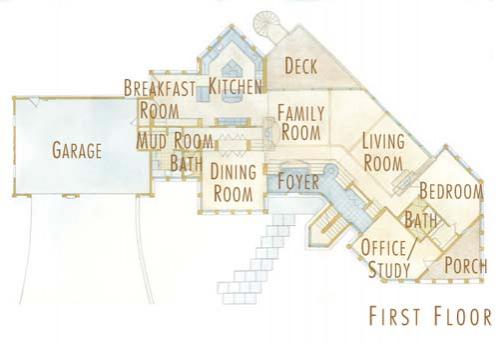

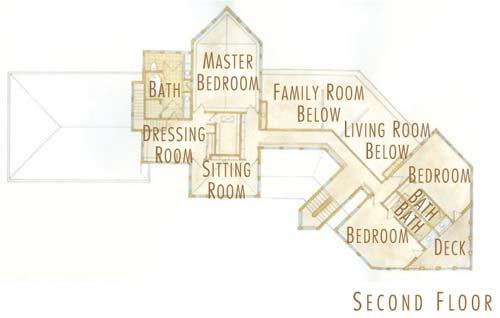

Our architect, Bob Wilkoff of Archaeon Architects, sited our home on one of the land's natural slopes to utilize the moderating effect of the Earth's temperature; this is one of the most energy-saving aspects of our home. In summer, it can be 10 degrees cooler on the lower level than in the upstairs bedrooms, so each July we move downstairs to our "summer home." In winter, the window placement and second-story overhang help us exploit the sun's warmth on our south-facing spaces.

The breakfast room's oval Saarinen Table—designed so no one gets stuck sitting over a leg—was given a restored Formica finish. Natural hemp slipcovers on the chairs, in Galbraith and Paul's "Donuts" fabric, feature hand-applied natural dyes.

To build the house, we contracted Jeff Carpenter, founder of the custom building company Monticello Homes in Fairfax Station. Although he had little green building experience (which was the case with most builders in this area a decade ago), Jeff was committed to building sustainably while staying within the project's budget. His homebuilding planning method was to budget each individual category: He gave us the estimated prices of the average conventional products we would need in each category, and we added our 5 percent premium to get each category's individual budget ceiling. When we were under budget in certain categories, we could put the excess funds toward another, more expensive item somewhere else. One of Jeff's biggest concerns was that his usual suppliers wouldn't carry recycled concrete, drywall, insulation and countertops. To our surprise, in many instances they did—without a premium price.

The kitchen has FSC-certified maple and wheatboard cabinets, and its counters are made of soapstone, a beautiful, stain-resistant surface that retains heat.

Searching for green

Although sometimes we located items very easily, finding green products for building and landscaping was a challenge. I used the Internet to track down essential items such as insulation, drywall and hardwood flooring, and our team relied heavily on the growing community of environmental groups to find resources. A nonprofit organization, Programme for Belize, for which I once raised conservation project funds, helped me find the ipê wood for our deck. The BuildingGreen suite of online tools, available by subscription at www.BuildingGreen.com, was vital; it includes a green products directory with more than 2,000 listings, along with case studies for $199. The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) was invaluable; it certifies wood products through the supply chain (www.FSCUS.org).

Green carpet proved difficult to find because so many brands include toxic glues, nylon or other environmentally harmful materials. I interviewed a dozen sales representatives to determine the fibers' post-consumer recycled content, what was in the backing and whether the carpet could be recycled after its useful life ended. Perseverance paid off, and I found a few companies—Lees, Shaw, Mohawk and Interface—that supplied responsible products for reasonable prices.

Occasional disappointments cropped up: Recycled roof shingles were absurdly expensive, and county regulations wouldn't allow us to have a green roof with live plants. To keep within our 5 percent rule, we opted for a conventional product—asphalt shingles—but we did choose the 40-year shingle, so at least we know the roof will last a long time. In addition, a company that agreed to supply locally mined soapstone for our kitchen counters reneged, forcing us to order from a Brazilian company at the last moment. I considered switching to recycled countertops but stuck with soapstone because it's beautiful and stain resistant, retains solar heat, and requires only a nontoxic mineral-oil finish.

What's inside counts

It was surprisingly easy to find appliances, furniture and décor that met our environmental, aesthetic and financial criteria. Barbara Hawthorn, an interior designer who once worked for the Environmental Protection Agency, helped us choose natural wood furniture and gorgeous eco-smart fabrics. She selected Knoll Textiles for our furniture upholstery because many of the styles have some reclaimed content or use natural fiber—and they're durable, which is important to a family with children.

The classic 1950s designs of the vintage chair and table blend well with the bedroom's new eco-friendly and recycled-fiber décor.

Barbara's and my design choices were rooted in our shared admiration for Modernist classics. Several of our tables are vintage pieces, rescued from yard sales. A childhood friend of Luke's used sustainably harvested wood and hand-applied nontoxic finishes to make our dining room table and an egg-shaped, hollow coffee table.

Our bedroom's wall-to-wall carpet, from Mohawk, is manufactured from 100 percent post-consumer recycled PET (polyethylene terephthalate) polyester. Thousands of soda bottles were melted down and spun into plush broadloom roll carpet. We splurged on natural wool area rugs in our great room and put recycled carpet from Lees Industries, headquartered nearby, in the bedrooms.

Well-planned lighting is key to minimizing energy use, and our fixtures use LEDs, compact fluorescents and other low-energy bulbs to create layers of light. Programmable dimmers help minimize energy use, as do the great room's electronic shades, which allow light in but block 97 percent of UV rays, protecting our furniture from sun bleaching. We can control the lights and shades remotely, allowing us to monitor lighting and temperature even when we're not home.

It was also easy to find water- and energy-efficient kitchen and bathroom fixtures, using the Energy Star label as a guide. When choosing kitchen cabinets, we weighed health and environmental concerns and chose Neil Kelly cabinets made from FSC-certified wood, delighted to spend less on them than we would have for their conventional counterparts. We put the leftover allowance in the cabinet category toward items with a higher green-product premium.

Zaneen Lighting's playful Medusa sconce is energy efficient—in three years the owners have not had to replace a light bulb. The chaise is a favorite place to read and enjoy the fireplace.

Worth the effort

The team met our 5 percent ecological product premium and waste-management goals and was re-warded for its efforts: In 2005, Monticello Homes and Archaeon Architects won a Monument Award for superior home design. The house also received a Best in Show nomination from the National Association of Home Builders for its environmental features. RTEC Treecare won an award from the Tree Care Industry Association for its tree-preservation work.

Our home-building odyssey inspired me to write the book Your Green Home: A Practical Guide to Eco-Friendly Building and Remodeling, which awaits a publisher. Our family now enjoys a happy, healthy, affordable home, and we sleep easy knowing it's a little lighter on the earth.

![A Tranquil Jungle House That Incorporates Japanese Ethos [Video]](/images/22/08/b-2ennetkmmnn_t.jpg)